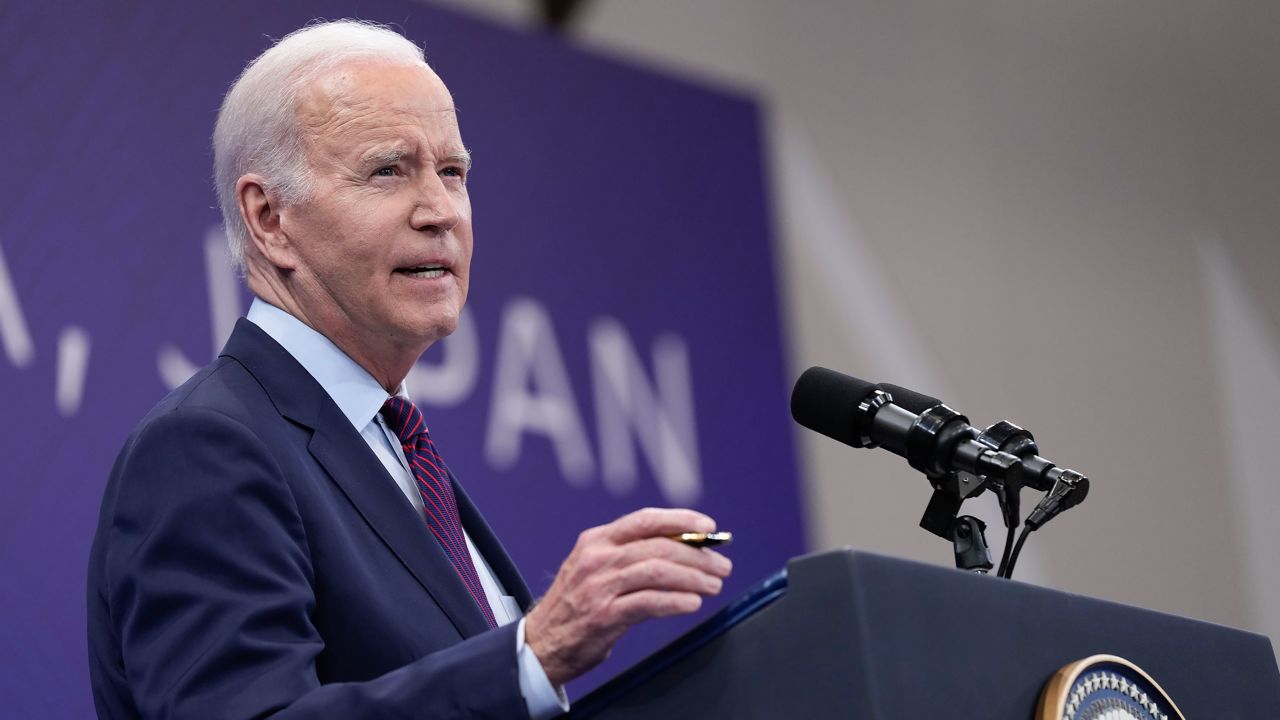

President Joe Biden ended the month of May the same way he began it: with a phone call to House Speaker Kevin McCarthy.

His first call invited McCarthy to the first in a series of meetings to negotiate an agreement on the debt ceiling and the budget. His latest came Wednesday night, after a bipartisan coalition in the House voted 314 to 117 to comfortably pass that agreement, moving the White House a critical step closer to dodging the kind of economic calamity that could derail two years of legislative progress – and a reelection campaign (the legislation now goes to the Senate where it’s expected to pass but timing for a vote is still unclear).

In between those events was a process that people involved acknowledged was far from certain to create the outcome it did. The weeks were defined by days of negotiations, several breakdowns, one slow-moving bike ride and, in the end, an effort that found two sides that started largely unfamiliar with one another unwilling to accept failure – and the sweeping repercussions that would bring.

It was an effort one White House official candidly acknowledged “was far more dangerous than people will recognize given the outcome.”

For each side, the process involved painful tradeoffs that earned them barbs from the right and left: Questions about why the process didn’t begin sooner, why alternative methods for raising the debt ceiling weren’t explored more fully and why the debt ceiling exists in the first place have all been raised in the aftermath.

But for now, with disaster likely averted, each side describes a process that proved illuminating in an era of diminishingly few bipartisan achievements.

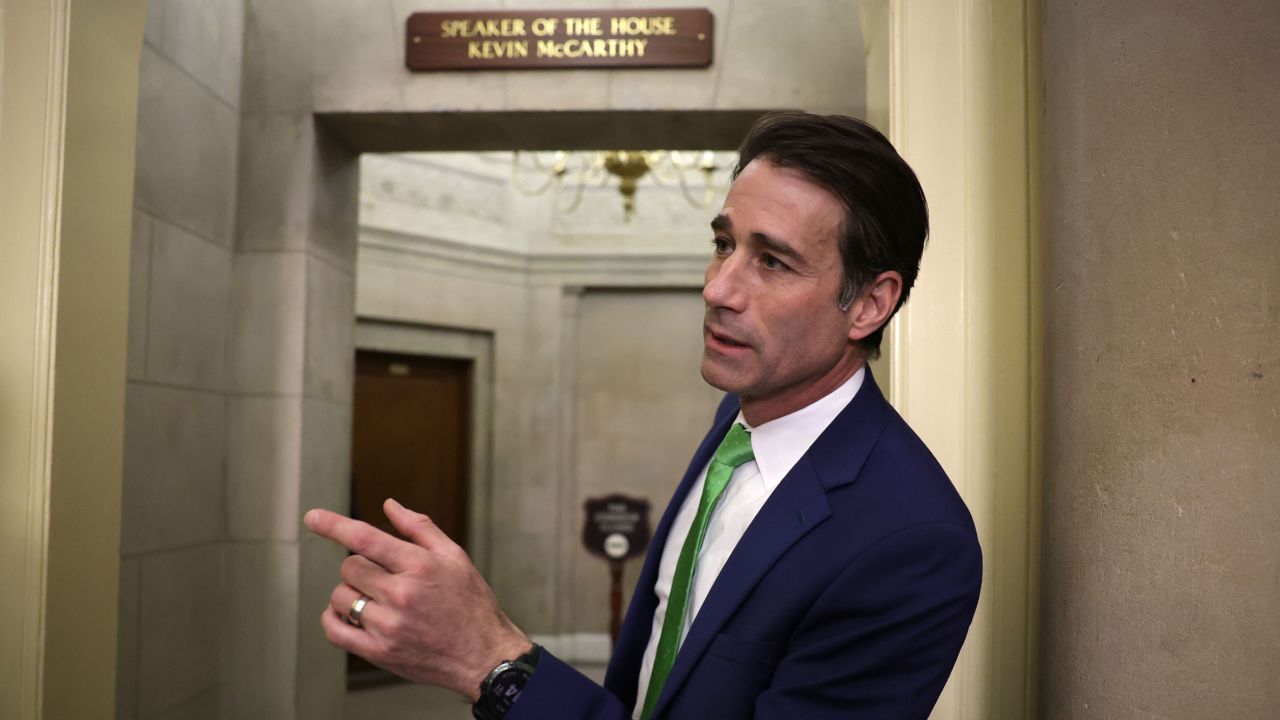

“You’ve got two Irish guys who don’t drink,” Rep. Patrick McHenry, one of the Republican negotiators who helped serve the deal, said of the relationship between Biden and McCarthy. “The bonding opportunities are not the same as for an Irish guy like me.”

Negotiations kicked into higher gear on May 16, after Biden appointed his counselor Steve Ricchetti and budget director Shalanda Young to lead negotiations alongside Legislative Affairs Director Louisa Terrell.

Young’s appointment, in particular, drew an immediate nod of approval from McCarthy, who pivoted from his seat in the Oval Office to look back at Young.

“She’s well respected by both sides,” McCarthy said of the former longtime House Appropriations Committee staffer, according to White House officials. “I think she’d be great.”

It didn’t hurt matters that Young hailed from Louisiana, the same state as Rep. Garret Graves, one of the Republicans appointed by McCarthy to hammer out an agreement. During talks, the two joked about who made a better gumbo (“She conceded,” Graves joked) and that Young’s father and Graves work out at the same gym.

When Young arrived in the Capitol for one of the first meetings between White House staff and the speaker’s office, she was spotted by GOP Rep. Tom Cole of Oklahoma, a longtime appropriator.

He could barely contain his excitement – and relief.

“I feel so much better knowing you’re in the room,” Cole said, as he embraced Young in a big hug.

The newly appointed White House trio began meeting with McCarthy’s negotiating team that night and met in person nearly every day from that point on, at times shuttling between both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue two to three times a day.

They shared late nights and meals, including a delivery of Call Your Mother bagel sandwiches during an especially critical four-hour long meeting last Thursday, courtesy of White House chief of staff Jeff Zients. Young and McHenry, who both have young children, called each other each morning while dropping off their children at daycare, White House officials said.

‘We were cut out, and they have work to do’

Throughout the negotiations, the trio of White House officials worked to keep the president, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries updated on a daily basis. Ricchetti, the senior-most member of the White House team, spoke regularly with McCarthy throughout the talks.

A veteran of three administrations who has been a constant presence by Biden’s side since his vice presidency, Ricchetti was also viewed as a critical conduit to and from Biden himself.

“It’s clear when he’s speaking, he’s speaking for the president,” a House Republican briefed regularly on the talks told CNN. “And when he’s listening, you know it’s going to get back to the president.”

Terrell was in constant contact with McCarthy’s chief of staff, Dan Meyer, a long-time Capitol Hill veteran who had already announced his intent to retire after the debt ceiling stalemate was resolved.

It was a team with experience, deployed in a carefully calibrated – and intentionally mapped out – series of options, breakdowns in talks and eventual path forward that would secure the sign off from Biden and, perhaps more critically, their House Republican counterparts.

But it was also a team that intentionally – much to the frustration of Democrats on Capitol Hill – kept the details of their work close to the vest. As McCarthy and his negotiators spoke daily, and often much more, to reporters as they sought to press their priorities, Biden and his team remained silent.

“Asking me about the communication (with the White House) implies there was communication,” one House Democrat said. “We were cut out, and they have work to do.”

But White House officials, while keenly aware of the work needed after the agreement was reached to read in Democratic members on the other side of Pennsylvania Avenue, said the posture was intentional – and driven by Biden.

“Their view is that there’s no upside to broadcasting the play-by-play,” another House Democrat, echoing widespread frustration inside the caucus, told CNN. “I happen to disagree with that view, but also recognize that they reached an outcome.”

White House officials also insisted, in repeated and painfully awkward public appearances, that they hadn’t deviated from Biden’s monthslong position of not negotiating over the debt ceiling.

That was exactly what they were doing, in large part because House Republicans had passed their own legislation despite significant skepticism – inside the White House and even among GOP members – that would be possible.

GOP negotiators believed they had room to cut deals with the White House, and they credit the speaker with giving them “the space” to do it. McHenry and Graves kept McCarthy constantly apprised, decamping to his office around the clock, walking with him to get Chipotle or in Graves’ case meeting up for a bike ride on the National Mall to hash out the details of what was on the table.

‘We had probably three major blowups’

Shortly after talks started, White House officials offered a proposal they knew would be rejected: A series of tax increases on high earners and corporations included in Biden’s budgets and a feature in his stump speeches on the debt limit that would bolster his deficit reduction bona fides.

Republicans, as they had long made clear, rejected the provisions – and any tax increases – out of hand and made little secret of their frustration over the play.

The back and forth elicited sharp responses from Republicans, who viewed the tactics as political and ignorant to the urgency of an acutely high stakes moment.

Negotiations broke down. And then broke down again.

White House officials were also faced with the reality of the presidency – and a scheduled three-stop foreign trip that landed right in the middle of the negotiations.

Biden ultimately decided to cancel two stops on the trip. But he viewed his travel to the Group of Seven summit in Hiroshima, Japan, as too critical in the midst of a tenuous geopolitical moment to miss.

For the White House negotiators, that meant late nights and early mornings. During the particularly turbulent third weekend of May, following a sudden pause in negotiations that Friday, White House officials briefed Biden at 9:30 p.m. on Saturday, reconvened for a 10 p.m. meeting, only to wake up and brief the president again at 4:30 a.m. the next morning, White House officials said.

Republican negotiators described tedious, long meetings where most of the time they “inched forward.”

On Friday, May 19, talks “blew up,” Graves remembered. The White House negotiators left Capitol Hill abruptly and for hours, it was unclear when the conversations would resume.

In one particularly tense moment, as the White House staff were deriding the GOP tax cuts bill and citing what Republicans felt was a questionable CBO score, one McCarthy staffer yelled across the table: “Bullsh*t.”

The White House contends Republicans offered up a proposal that amounted to a list of Republican positions that were nonstarters for Biden.

After the meeting, the negotiators decided to put a “pause” on the talks, giving everyone a much-needed opportunity to cool down.

“We had probably three major blowups in this negotiation, one of which was that Friday,” McHenry said.

At the time, Graves said the spending side of the negotiations were at a logjam. He and McHenry – despite their wide latitude in the talks — had been given an explicit order by McCarthy. They were to spend less money in 2024 than in 2023 on domestic priorities.

“The White House position at time is that they were going to spend more money,” Graves remembered. “Those things directly contradict. On that Friday, the White House took about two steps backwards in negotiations.”

The negotiations up until that point had been closely held.

“Our intention was just to negotiate in the room, work things out,” McHenry said.

But he recalled that it was around this time “we said publicly our private frustrations.”

As negotiations appeared to offer little path forward, Biden made plans to call McCarthy aboard Air Force One on his way back to the US.

The most powerful Democrat and Republican in the country both recounted the conversation as cordial and businesslike. Biden made a point of briefing McCarthy on the summit itself.

But it also marked a critical turn for the talks themselves. Quietly, White House negotiators had never actually stopped talking to their Republican counterparts. Methodically, with engagement both teams repeatedly called fair and professional, the groundwork was laid for the multi-day sprint ahead.

Where rank-and-file Democrats insisted they were kept in the dark, Biden insisted on maintaining a clear and united front with Democratic leaders, officials said.

When the negotiators reconvened after Biden’s return, White House officials suggested a change in venue. The Republicans were invited to the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, where Young has her office.

Over the course of four hours – and the sandwiches sent from Zients – the negotiators moved through the key pillars of the deal. After the meeting ended, McHenry stayed on campus, walking across West Executive Avenue and into the West Wing to continue meeting with Ricchetti for another hour.

Negotiators worked around the clock, but there were times when outside life events came calling. Graves had to attend a personal matter, forcing him to even miss a Monday night votes series. McHenry, who at times throughout the process had his small children in tow, attended his neighbor’s kid’s birthday party last weekend, which he jokingly described as a “two-year-old rager” when he returned back to the Capitol.

And during a critical moment in the negotiations, Graves and Young – both Louisianans – attended a White House event celebrating the LSU Tigers, the 2023 NCAA women’s basketball champs.

Graves confirmed that the two talked shop at the event, calling it “a very candid conversation about how we’re going to move forward, if we’re going to be able to come together and ultimately get a deal.”

The Saturday morning before the debt ceiling deal would come together, Graves met McCarthy on the National Mall for a bike ride to brief him on the emerging agreement.

“It was a meeting on wheels,” Graves said.

The ride was tedious, however, such that Graves, who shares his exercise data with members of his family, heard from his son, harassing him about “riding so slow.”

“He was hazing me about our speed,” Graves joked, pulling up data showing his 9.8 mile ride took him 45 minutes.

‘This was no easy task to get here’

As the negotiators worked through the final, and exceedingly thorny, issues outstanding, Biden started to turn his attention to calling key Democrats in search of votes and voices of public support. Over the weekend, he spoke with Rep. Jim Clyburn, the South Carolina Democrat and close ally who helped save Biden’s 2020 campaign. Clyburn soon hit the airwaves to talk up the deal.

After Rep. Annie Kuster, the chairwoman of the 99-member strong New Democrat Coalition, endorsed the bipartisan deal in a statement Monday, Biden called to thank her for support, talking up the benefits of the deal and the key Democratic priorities he was able to protect from Republican spending cuts.

“We talked about how we would work together to get the votes to get it passed,” Kuster told CNN. “We both agreed that this was not an ideal circumstance to be in, but once we went to work and really put our shoulder to the wheel that the outcome in terms of protecting the programs that are so important to our constituents was very positive.”

While Biden made some key calls, a dozen senior administration officials hit the phones, making more than 100 one-on-one calls to Democratic lawmakers ahead of the House vote.

A series of briefings were set up for congressional Democrats, many still seething about their contention they were boxed out of the talks.

The blowback from progressives wasn’t a surprise, officials made clear. They both expected and – even if they viewed the deal as a positive outcome – understood.

As Biden’s senior officials gathered behind closed doors in the Capitol to brief House Democrats, the lawmakers proceeded to give Young two standing ovations for her efforts.

As for Young, she made clear she was looking forward to spending time with her young daughter again and, after being spotted by reporters with a Nordstrom Rack bag in an emergency effort to address a lapsed dry-cleaning routine, perhaps do some laundry as well.

There was work to do with Democratic lawmakers and the Appropriations process and its deadline would be bearing down soon enough. For the moment, however, the exceedingly real risk of economic – and political – devastation posed by default had been taken off the table.

“I can assure you that this was no easy task to get here, but what was on the line for the American people was real,” Young said this week. “I know I breathed a little easier – I called my parents, told them to breathe a little easier – that a deal had been reached. And that’s what this was all about.”